photo by John Fujii © 2017 ACM SIGGRAPH

The theater is sold out.

People with tickets mill about, talking quietly, the curtains of the theater just steps away. A few hopefuls wait in case someone doesn’t show up. The marquee lights light up everyone. Sounds from the Immersive Pavilion and Exhibition roar over the soon to be viewers.

At last, the curtain parts; the announcer tells them they can go in.

People eagerly file in one by one, discussions quietly trailing off. They sit down and then…

…I strap a brick on their face.

Welcome to the VR Theater.

We don’t actually strap bricks on faces in the VR Theater, of course. That, is one of the frequent misunderstandings about virtual reality (VR). Its very name is another. And, yet another oddity is the way people often dismiss VR “until it looks real”. It doesn’t have to be real, at least in the eye of the beholder.

Many of the people who have come to the VR Theater at past SIGGRAPH conferences are seeing VR for the first time, experiencing not only the amazing art and emotionally moving pieces — which, after all, are the hallmark of SIGGRAPH — but VR itself.

Nearly everyone leaves both moved and with a better understanding about what VR “really” is.

I’ve been going to SIGGRAPH longer than I care to admit — and I find the amount of delighted exploration from newcomers in the VR Theater fascinating. I’ve seen people who have literally invented the lexicon of graphics be confronted with something brand new that they’ve never experienced. I’ve also seen old hands at VR smile with delight to see something artistic.

What are some common misconceptions that the VR Theater dispels?

People talk about someone being “virtually a saint” or say that a car is “virtually silent”. Most people think the “V” in VR means the same type of virtual — virtually reality, nearly real, an alternate reality. That isn’t what VR means at all. The name is actually a play on words. It means “virtual” in the computer-science sense of the word; more flexible than what it virtualizes.

In our case, more flexible than reality.

VR, thus, gives people the ability to create wonderful artworks, with creativity that is unbound by the possible. Creative, imaginary worlds that participants can actually experience, and go “into”. Art is about creating an experience. SIGGRAPH has always brought that art to the computer graphics community via science. To me, this is one of the things SIGGRAPH has always meant: a blend of the scientific and the artistic. It takes a lot of science and engineering to pull off VR, but it’s matured to a point today that art can set it free. Art that will “seem real”.

This is another dichotomy. Many people see pictures of VR and think, “Well, it doesn’t really look all that real. I’ll wait.” Or, they see 360-degree video and say, “Now that looks real.” They put it on and like it, but aren’t wowed by it.

VR doesn’t have to look real to seem real. I used to say 360-degree videos weren’t “really” real VR (lame pun intended). I’ve recanted my position. Regardless of what’s “real” (apologies for another pun), both are perfectly valid art forms. I briefly tried to coin the term “FR” for Filmed Reality, but 360-degree video looks real. In particular, VR of the filmed kind won’t trigger the uncanny valley effect, so this type of VR is great for emotional pieces, training, virtual tourism, and connecting with fellow humans. There is a very real place for this.

On the other hand, with what special effects creators would call “the CGI kind of VR”, you have VR worlds that are generated with real-time graphics. These worlds are what I now call “full dive VR”. These worlds don’t necessarily look real, but they seem absolutely real.

We have 11 senses (more or less). By far the largest input to our sense of reality, for most people, is sight; following that, sound. These two senses are complimentary. In VR, if you hear a sound behind you, your brain will assume something is behind you; when you turn and see it, it reinforces the sense of reality.

It will scare you — for real.

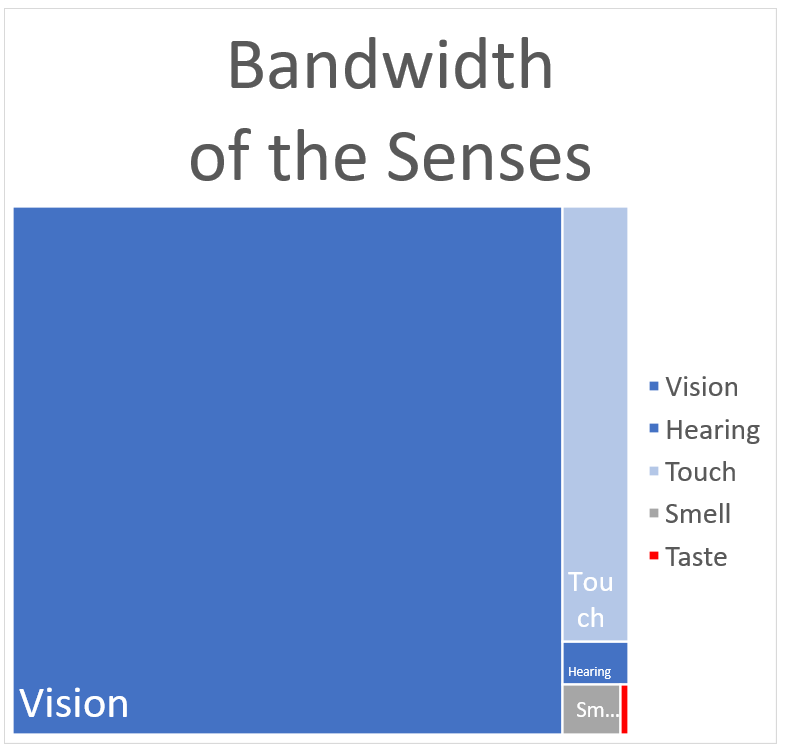

Quantifying how much bandwidth your senses represent for comparison is difficult, as our sensorium works in a variety of odd ways. Tor Retarders did some research on this, and, using the rough numbers that he came up with, I built this heat map:

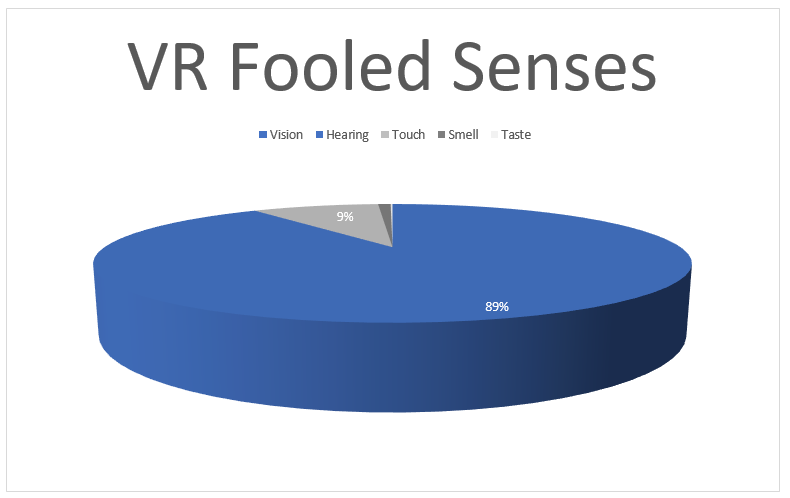

Do we really need to taste a zombie world? It turns out, we don’t need all of these senses to build a sense of reality. If we turn around the above chart and look at VR fooled senses, we see why we really do have “Full Dive” VR today. Virtually real senses are in blue:

No, you won’t be able to eat that steak in VR yet, but when you hear that noise behind you, turn and see a large being in the woods, even if it’s cartoonish, you’ll feel a thrill, deep to your core. (Much like in Baobab’s delightful 2019 selection “Bonfire”.)

Watching this kind of experience on YouTube (as embedded above) just isn’t the same as feeling its reality by wearing the head-mounted display, or HMD.

Speaking of HMDs, I said, half-jokingly, that we strap bricks to faces in the VR Theater. One objection participants have to VR is that it’s too isolating, or the hardware is too heavy. Due to physics, HMDs need to be relatively bulky so that users can focus on optics. An HMD is still less than one quarter the weight of a combat helmet. One saves your life, and the other shows you a new life. The size and weight will improve over time. Recently, I saw a laser prototype that was intended for augmented reality but shows a lot of promise for VR.

The larger issue that strikes most people is that a VR HMD, also referred to popularly as a “headset”, is isolating. Nothing could be further from the truth. A VR Headset doesn’t isolate you; it propels you into a setting, into a world. No, you don’t change planes of reality — you can always reach up and pull it off — but a VR headset is anything but isolating.

Unless, of course, you’re standing outside the person with the headset on. This is why those product warnings are so very important. SIGGRAPH carefully designed its VR Theater so that people, if they stay seated, do not smash into walls or desks, or inadvertently bump into others.

It’s been wonderful to see reactions of people trying it for the first time, and engaging with the stories. For example, we had one person scream and jump out of their seat; their reaction was very real, very visceral. This, to me, is why VR is an extremely powerful medium to explore art, the human condition, and build emotionally, impactful experiences. We do have full-dive VR: You think it’s so real, you jump out of your seat.

I am hopeful to help more people experience the magic of the VR Theater when it’s safe to gather again. In the meantime, the volunteers behind the scenes (myself included) are experimenting with ways to deliver delightful content from our SIGGRAPH 2020 contributors to those of you who can experience it.

Dive in to VR — the water is great and you won’t even get wet.

John Gwinner is CTO of CareLabs Healthcare and a member of the SIGGRAPH 2020 VR Theater subcommittee. He holds a B.S. in electrical engineering from Cornell University.