National Film Board of Canada

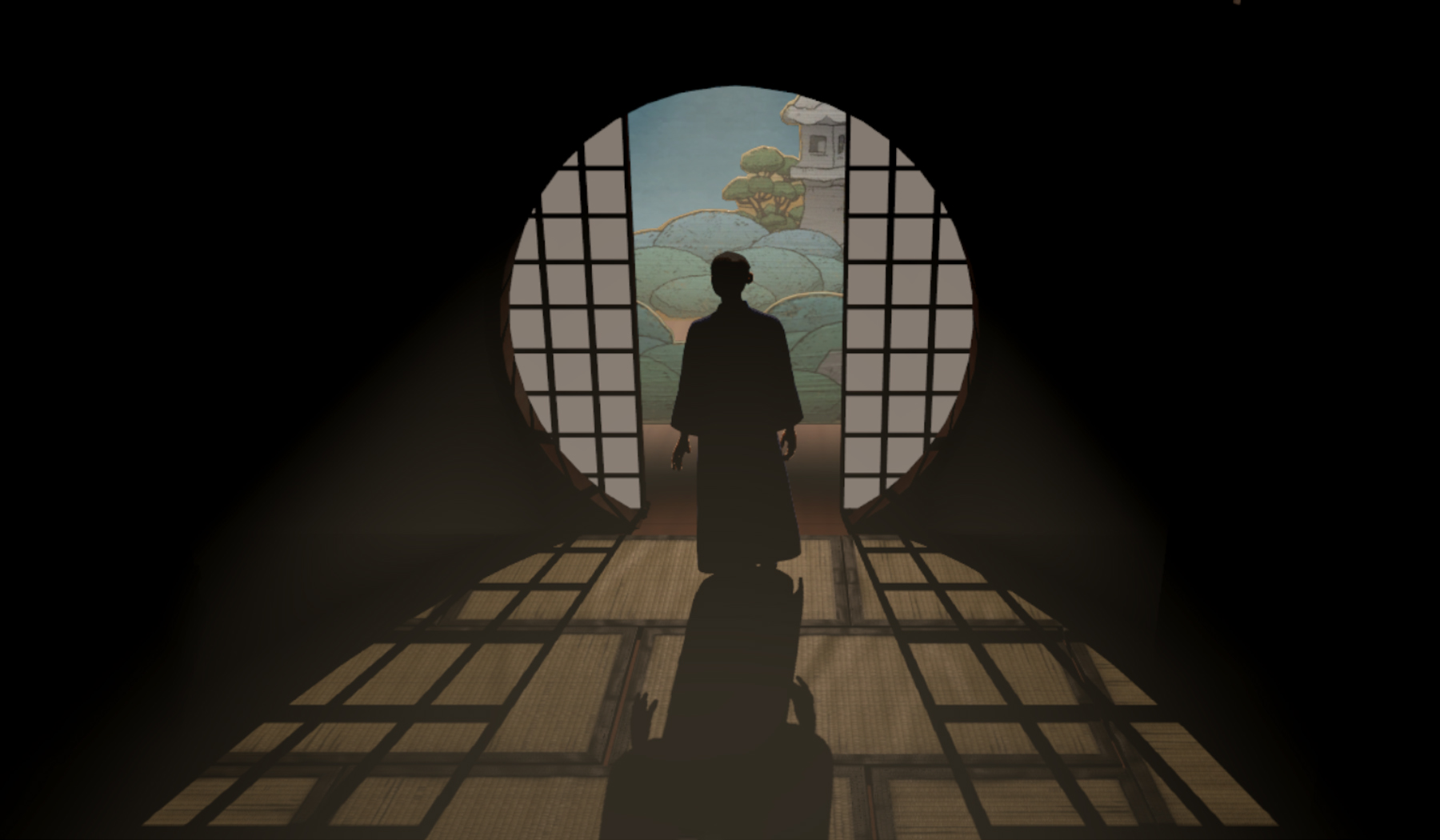

Blending family archives and the latest in virtual reality (VR) technology, “The Book of Distance” uses spectacular storytelling to immerse audiences in an experience through one man’s journey leaving his home in Hiroshima, Japan in 1935 to start a new life in Canada. This intimate and thought-provoking narrative, encompassed by state-sanctioned racism and broken memories, is told by his grandson, Director Randall Okita. We caught up with Randall and Producer David Oppenheim to learn more about their process and what to expect from this SIGGRAPH 2020 Immersive Pavilion selection.

SIGGRAPH: Talk a bit about the process for developing your experience, “The Book of Distance.” What empowered you to tell this story?

David Oppenheim (DO): This is exactly the kind of story and approach to storytelling that the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) has embedded in its DNA. The NFB is a public producer with a series of production studios across the country. Ever since it was formed over 80 years ago, the NFB has placed storytelling, specifically technology in the service of storytelling, at the heart of what it does. For context, the NFB produces creative documentaries, auteur animation, interactive stories, and participatory experiences. Another core desire of the organization is to work with artists and allow them to experiment, while elevating points of view that haven’t been historically represented. All of these different components are behind the final story we developed.

Randall Okita (RO): A couple of different things empowered me to tell this story. Part of it came from living with these stories, pieces of my grandparents’ story, over the years, including the questions that were embedded in the parts that I know and that come from the parts that I don’t know or have been imagining. Like many of us, I’ve always had a great curiosity, pride, and interest in my family’s history and the stories that are woven through it.

In terms of project development, I already had some background in making films, sculptures, and installations, and David and I had previously made a film together. We started talking about this medium, experimenting, and testing. We discussed what might be possible, and David started asking key questions, creating a space to ask more questions. Combining all of this with how it felt to be working through the elements in VR — how it felt to be moving around — allowed creating this story to become uniquely possible in the VR medium right now.

SIGGRAPH: How long did the project take? How many people were involved?

DO: The core team in the production phase was made up of 10 people. Some of these 10 people were also involved throughout the beginning ideation and development stages, which took place over a couple of years. At all of the different stages, we worked with small, core teams, starting with a series of experiments in the summer of 2016.

The NFB and our studio have been working in the field of interactive storytelling since around 2007, but we hadn’t made any VR, so we were following this second or third wave of VR with the Oculus Rift DK1. During that summer of 2016, we thought we’d start getting our hands dirty by inviting four artists that we’d worked with before into the studio to ask them both technical and creative questions about the medium, and just start experimenting without a particular story in mind.

We knew Randall because he’d worked with our animation studio on a beautiful short film called “The Weatherman and the Shadowboxer“, and we also knew about his work in sculpture and installation, so we thought he would be a really interesting artist to interrogate on using VR as a creative and technical medium. We started with an experiment that summer, which would end up evolving into “The Book of Distance”. We spent about two years on this ideation, prototyping, and production aspect.

I’d say the whole piece unfolded over about four years. We just launched the project at Sundance in January 2020.

RO: One of the things that was unique and special about this process is the timeline and the fact that we worked in these phases, with each phase having its own goals and questions. This allowed us adequate time to consider and answer questions before moving on to the next phase. It also allowed us to work with different artists at different times, due to availability or specific goals, and we got to ask big, important questions about what was and wasn’t working.

This process also empowered us in a way, as we were allowed to feel and discover how different elements felt in this space. Everything was so new, and we really wanted to provide our audience with a connected, emotional experience, and we didn’t have preexisting language or a roadmap to do this. That’s how we eventually came to the idea of aiming to engage our stories and our histories with an active imagination — as a physical, participatory experience — and, of course, embracing all of the challenges that come with that, which became part of the adventure.

SIGGRAPH: Speaking of challenges, what was the biggest one you faced?

DO: For me, the VR technology was relatively new, so working with the affordances of the medium to elevate the story and essentially make the technology disappear was probably the biggest challenge. The NFB has also been wrestling with this throughout its history, to have technology be in the service of story, and that’s always a challenge if you want to do it successfully.

From a user experience design point of view, we set out wanting to tell a powerful story, and balancing this with agency was a challenge that we kept revisiting. Normally, linear storytelling is what leads to a powerful story, so how do you stay true to that while using amazing technology that’s allowing people to interact in a physical space, in a virtual space, where you can pick things up, touch, and hold them? It really is a challenge in any sort of interactive storytelling, and it has its unique challenges within VR specific to the language.

RO: I definitely cosign all of that. I think my biggest challenge was the dance between both involving the audience, and also sharing with them in a way that feels coherent and natural. The extension of that for me was then trying to be vulnerable in the sharing of some personal moments and trying to understand and consider how to do that in a useful, connected way. When it comes to personal storytelling in this vein, that’s always the challenge. You need to really trust the team around you to try to answer the questions that you’re asking yourself as you go through this process.

DO: I would also add that the technical team fought through their own roadblocks as well, under Randall’s creative guidance. For example, when working through rendering human beings in the virtual space, we looked at the various ways that other teams were doing this and experimented with everything from more photorealistic humans to videogrammetry, resulting in our current art style.

We leaned into the tips and tricks of our programmers and artists, but we also tried to embrace the limitations of the technology in a way that worked to elevate the story, rather than detract from it. For example, we chose a minimalist theater aesthetic, which influenced our human beings in that the art style was more focused on their presence, scenes, and watching them interact versus trying to render a realistic human face that spoke and had all of the standard features. There were many situations similar to this one where we faced challenges, but chose to focus on how to work with the given constraints in a smart way that put story before brute force in terms of technological fixes.

SIGGRAPH: From a technical standpoint, how did you manage to blend family archives with today’s advanced technology?

RO: As David mentioned, we tried to focus on the story we were telling instead of trying to solve every problem. This led us to embracing the questions that we have about what happened, including those that stem from what we do know through archival, tactile documentary touchpoints. From these, we developed this art style, which comes from the language of magical theater and is connected to the sculptural and cinematic experiences that we could draw from.

We also wanted to clearly announce that this was our imagination; these are the parts that we don’t know about. We, along with you the audience, are imagining this space in order to fill in the questions that we have. We invite the audience to participate in creating the emotional experience and feel those moments. Then, it becomes an adventure — you’re removed from the place that you’ve come to know as home and you’re sent somewhere else.

DO: Specifically from a technical standpoint regarding the archives, the blending focused on taking those 2D scans and making them as high resolution as possible. They were then blended into the entire scene in Unity and to match the art style. Small details allowed the photos to feel like they belonged in that three-dimensional space.

For example, there’s a scene, a moment on the farm, when you press the camera. Previously, you had done that in the house in Hiroshima at the beginning of the scene, but you were taking a photo of our 3D-modeled characters. That’s the photo that then shows up like an old Kodak insta-photo. With the archival photo that we bring into the scene later on, the mechanic is the same: You press the camera and the photo shows up. This time, it’s an archival photo from Randall’s family — it’s 2D, black and white, but it’s surrounded by a frame and is a physical 3D object in the farm scene.

A lot of people have commented on the way those 2D photos have felt that they’re part of the three-dimensional world in a way that they hadn’t seen before. This concept was a creative approach to the constraints more than anything else, and it helped successfully integrate those archives into the 3D scene.

SIGGRAPH: You briefly mentioned the use of Unity. Why did the team choose Unity over other platforms? How did the platform serve the story?

DO: We touched base with our technical team to explain this one. Luke Ruminski, lead programmer on the production team used Unity to set up a continuous iteration build server. This was crucial because at the peak of “The Book of Distance” production, our production team was pushing upwards of 25 builds a day with iterative changes, and that would not have been possible without having an automated build server. It saved us hundreds of build hours, and allowed us to conduct rapid iterative testing.

Unity is also a game engine that largely supports VR projects through its vast features. This popularity makes it easier build a strong team of artists and developers who are familiar with the Unity ecosystem.

Unity’s Timeline was also an extremely useful tool for our developers, allowing us to quickly iterate on animation. We had a lean team with two programmers and over a hundred animations — Timeline made their lives much easier by allowing them to drop in motion-capture clips and blend them together inside the Unity engine, which is essential for a project that includes interactivity. The script for The Book of Distance was also very fluid and iterative throughout the production process, and Timeline helped us to adapt quickly to edits; since these changes would effect on our environments, animation and timing. Towards the end of production, our team was recording motion capture monthly and blending these animations together in the project as needed. Some good example of this include the scenes on the family farm in British Columbia, and the ending scene where Randall is talking about his grandfather’s life after the war. Both of these scenes had several rounds of animation, and included blends of linear and looping animations that allowed us to tell a fluid story and create an interactive narrative experience.

RO: The team also used Unity’s Universal Render Pipeline (URP). Michael Sebele, one of “The Book of Distance” programmers, enjoyed implementing URP during the projects optimization phase. URP was key for us to maintain our visual style while also remaining performant. The Book of Distance uses lighting and spotlights throughout the experience, and it was very important that we didn’t need to bake our lights and were able to keep them dynamic. Mike Sebele, programmer, was inspired to dive even further into URP to understand more about how it calculated the lighting, and other elements in our experience like fog. Mike was also inspired to ensure that URP would work with our Flat Kit shader, which was the stylistic preference for all of the characters in our experience.

We started with Unity 2018 LTS and are currently working with Unity 2019 for the additional URP updates.

SIGGRAPH: Randall, what was it like performing that motion capture for your grandfather? How did that come to be?

RO: It was one of my favorite parts. We looked at all kinds of different techniques and processes for creating the style of our characters and how to integrate movement. Initially, we did a quick cast just to illustrate what we were going for, and we were originally going to hire actors to do a different version of the motion capture, but it became a really special and unique part of the experience.

I know my grandfather’s postures, mannerisms, and how he walked. To have the experience of embodying that and imaging him as a younger man than how I knew him when he was alive just became extremely special, meaningful, and core to this piece. The capture of motion is also such a beautiful part of the language of this medium, and being able to see and observe that movement in front of you is so powerful, especially for a lead character who doesn’t say much, but whom you follow throughout the story.

SIGGRAPH: What emotions and thoughts do you hope to evoke from participants?

RO: My dream and my hope is to share my family’s story in a way that honors it and allows people to connect with it, creating an emotional reaction. It’s such a wonderful experience when I get to see or hear about the story resonating with people and having it bring up thoughts and feelings about their own histories. People tell me about their own shoeboxes of letters or photographs, in which they uncover both some answered and unanswered questions. Hearing these people start to ask important questions, even knowing they may not find certainty, is so special. To have them come out of the experience and ignite those sparks of engagement is the wonderful dream.

SIGGRPAH: What’s next for “The Book of Distance”?

DO: SIGGRAPH 2020 will be chance for us to put the piece in front of SIGGRAPH’s amazing mix of creative and technical folks. We’re also looking at a few additional festivals, and, at the same time, preparing for the online launch of the project in the fall, which includes doing a couple of other language versions. As of now, the piece will be available in English, French, and Japanese.

We’re also preparing for the online launch in the midst of a pandemic, so we’re looking for champions and supporters of the project to help lift it up and draw some attention. We’re off to a good start, but there’s a lot more work to be done in order to get the attention of an industry that’s often dominated by VR games; however, narrative VR storytelling is really coming to the foreground.

We certainly have plans as COVID-19 restrictions lift to find homes for “The Book the Distance” in venues and museums, too. We hope that’s part of the piece’s trajectory, certainly in terms of the focus on a North American audience with the shared history between the U.S. and Canada in terms of this story, but there is also a universal narrative that this piece brings out.

RO: We’re also just excited to try and find the best way share it with as many people as possible — share it with the communities that are historically involved; share it with a young audience that might not have the chance to experience it at festivals. We want to get it into homes, schools, and cultural centers. We need to continue having these conversations about telling stories.

DO: For us, in terms of education, this is a way of engaging with history. It’s not about memorization. It’s a visceral, physical experience that’s very much alive. This aspect is crucial in connecting with the younger audience, and we hope it’s in this story’s future.

SIGGRPAH: What are you most looking forward to in participating in your first SIGGRAPH conference!

DO: I’ve followed the SIGGRAPH conference super closely for years. I was involved in a project in 2007 with a collaborator who is a SIGGRAPH regular. He wrote up our project and it was presented at the conference as a technical paper. I wasn’t able to attend, but since then I’ve followed the conference every year and tried to consume what I can online. I’ve always seen it as a fantastic, creative laboratory of science and art, so I’m super excited for my first time.

RO: This will be my first SIGGRAPH as well. I’ve always followed the conference, too, and been interested, but I haven’t attended before. I’m just excited to be a part of the event; I’m excited to see how it works virtually and connect with this incredible, international community. I’m ready to meet people virtually, have conversations, attend workshops, share the work, and be able to experience other work. Being able to connect with the SIGGRAPH community and just hear what other people are doing in terms of story — experiencing story at this level of quality — is so very exciting.

DO: I definitely think it’ll be a challenge to recreate some of what festivals and conferences in a physical space have, which is that serendipity, but I look forward to how the conference handles that. Knowing SIGGRAPH, I’m sure it’ll be in a creative way. I think there’s the opportunity for people to meet others who they might not have in a physical setting where you may gravitate to the people that you’ve already met or know. I’m also looking forward to the opportunity that a virtual conference could provide. Then, there’s that huge potential to broaden the audience and make sessions available to more people, and to different people from different disciplines, that might not have had a chance to go to SIGGRAPH before.

RO: It’s going to be exciting to see how these virtual components go, especially for somebody new. It definitely opens the playing field in a new way. It’s new for a lot of people and organizations, this time that we’re in, but, like any project, it’s about trying, experimenting, and seeing what the evolution looks like.

SIGGRAPH: What advice do you have for someone looking to submit to the Immersive Pavilion for a future SIGGRAPH conference?

DO: I might have more advice after we go through our first SIGGRAPH! In our submission, we just tried to find a way to put the actual work forward, while also giving it some wider context in our written submission for people who hadn’t spent years working on the piece. Reviewers also have very little time with the amount of work they review, so in conveying a sense of excitement about the piece, we also tried to be concise. And then, of course, we made sure that the build that we sent in was as bulletproof as possible and that the technical specs were really well communicated.

RO: I would just reiterate: Always make something that’s meaningful to you with a team that is unafraid to challenge you and ask those tough questions with you. If you’re making something you and your team care about, you’re going put your best foot forward.

Randall Okita is a Canadian artist and filmmaker whose work employs sculpture, technology, physically challenging performances or stunt work, and rich cinematography. His work has been shown in both group and solo exhibitions, awarded internationally, and screened at festivals around the world, including retrospective screenings of his short-film catalogue in San Francisco and Toronto. Born and raised in Calgary, Alberta, Okita lives and works in Toronto and Japan.

David Oppenheim is a producer at the National Film Board of Canada’s Ontario Studio where his recent credits include: “The Book of Distance” (Sundance New Frontier, Tribeca Immersive, Hot Docs International Documentary Festival, CannesXR, SIGGRAPH); “Draw Me Close” (Tribeca Storyscapes, Venice Film Festival); the Webby Award-winning “Universe Within”, the final chapter of NFB’s Highrise project; and, the interactive documentary “The Space We Hold”, which was awarded the Peabody-Facebook Futures of Media Award, the Best Original Interactive Production at the Canadian Screen Awards, and the Columbia University Digital Dozen Storytelling Award. David is currently producing a number of creative nonfiction film and interactive storytelling projects as well as leading the studio’s XR lab. He is a past resident at the Canadian Film Centre’s Media Lab.