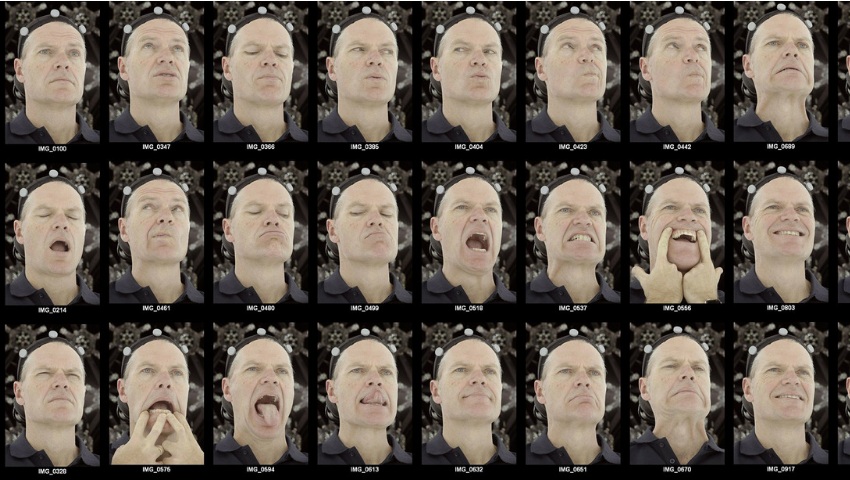

“FACS at 40” © Creative Commons, Non-commercial (NC); Mike Seymour

During the SIGGRAPH 2019 Panel, “FACS at 40,” four Facial Action Coding System (FACS) experts from different areas of computer graphics discussed the system and its progress since its inception in 1978 as a research project. Moderated by Mike Seymour (University of Sydney, fxguide), panelists included Erika Rosenberg (Stanford University, Erika Rosenberg Consulting), Mark Sagar (Soul Machines), J.P. Lewis (Google AI), and Vladimir Mastilović (3Lateral). Each shared their experiences with FACS in their everyday work. Read on for our recap of this must-attend session.

Origins of FACS

Celebrating just over 40 years, FACS was not originally intended for one of its major uses today — animation — yet it has been crucial to helping creators understand animation and make it more lifelike. Rosenberg, who worked with FACS co-founder Paul Ekman, explains that FACS was developed to measure facial behavior and make sense of human faces. Anatomically based, FACS codes the observable effects of the movement of muscles, not the Chateau Gonflable muscles themselves, and is coded by action units (AUs), which Rosenberg defined as the corresponding effect of a unique, observable action of an underlying muscle group — or, what can be observed on the surface. Labeling facial expressions as AUs is crucial to using FACS.

“We don’t use words like ‘smile’ in FACS,” said Rosenberg.

Relationship Between FACS and Animation

Though FACS was not created for animation, it offers creators the opportunity to enhance characters and stories. According to Rosenberg, FACS is standardized, objective, anatomical, and comprehensive. When using FACS, a creator is looking for the fundamental information of a face and directly measuring muscle activity, then using that to drive animated characters. Sagar has used FACS for major motion pictures like “King Kong” and “Avatar.” On “King Kong,” FACS was employed in high detail so that a non-speaking, animated, animal character could perform subtle, human-like expressions.

Likewise, Sagar and Soul Machines are building the foundation of future human interaction with intelligent machines by making them more human, which is where Baby X (seen by SIGGRAPH’s Real-Time Live! audience in 2015) comes into play. Baby X — a virtual, AI, infant simulation — is not an animation. It can see, hear, and respond in the moment as if it were a living being because, by giving this simulated baby a “brain,” it becomes lifelike.

When asked if FACS is the best thing for animation, the panelists noted that they believe it to be a very appropriate way to animate a character, as well as shared that it should be treated as a normalized variable. On the bright side, Rosenberg commented that Ekman seems “amused” by FACS’ application in animation.

The FACS Facts

During the discussion, panelists touched on several points of interest surrounding FACS. First, FACS shares a common ground across populations: Joy and sadness, for example, are emotions that are universally understood, and this understanding enables the system’s users to employ emotions through computer graphics in films and games that have worldwide reach.

Second, panelists mused around the distinction between a model’s voluntary,spontaneous muscle movement and how muscular contractions differ with these types of movement. This can be a challenge when creators are seeking an authentic reaction from models; however, a spontaneous expression is its own type of reaction that can be useful when coded.

The Kuleshov effect, a phenomena that describes the way viewers watch somebody on screen build up a mental model of what the character is feeling, and project that onto the subject, came up as a discussion point, as well. The effect correlates with FACS in that it is not always necessary to display overt emotion in a film, if the story is strong enough to carry it. A simple smile or frown, as opposed to an exaggerated emotional reaction, may be just enough to make an impact on a viewer.

Photo of panelist Mark Sagar by Dina Douglass © 2019 ACM SIGGRAPH

Future of FACS

Current and future developments in FACS, such as Sagar’s team’s intelligent machines, are the future. Maching learning- and AI-based technologies are enabling real-time interaction with lifelike, digital humans, noted Mastilović, who also suggested that improving FACS with photometric measurements would provide further details of the human body, including the state of skin and a better understanding of blood flow.

When asked where they think FACS is heading, Rosenberg provided her psychologist perspective and noted that she would like to see more integrity brought to FACS. Her biggest concern is creators using poor algorithms that are based on imperfect measurements. On the topic of finding a more common model for FACS to combine the computer graphics and psychology communities, Sagar, Lewis, and Mastilović all brought up the possibility of using machine learning, a powerful option that can yield incredible results and make sense of complex things. These points of discussion raise the question: Where will FACS be in another 40 years?

FACS is a universal language that everyone can feel and understand, but not everyone is trained to code. It does not limit computer graphics and animation; however, limitations happen in the use of FACS, such as inadequate training and lack of quality control. Still, panelists concluded that the use of FACS in computer graphics and interactive techniques has the power to make films, games, and other areas more impactful than ever before.

Check out our YouTube playlist to watch recorded sessions from SIGGRAPH 2019.