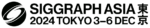

Graphic Recording of the SIGGRAPH 2018 Business Symposium “Academic and Industry Partnership” panel by Jason Toal

The SIGGRAPH 2018 Business Symposium “Academic and Industry Partnership” session was a combined panel and roundtable discussion, and consisted of panelists ranging from researchers embedded at post-secondary institutions to UX design leads. The panelists included Neil Randall, director, Game Institute at Waterloo University; Charla Pereira, senior UX designer, Microsoft HoloLens; Dr. Alan Kingstone, UBC Psychology; and, Dr. Cydney Nielsen, senior designer, Microsoft Design. Discussions among the group focused on identifying what research needs a company might have and developing an understanding as to what shared needs (between industry and academics) might lead to win-win partnerships.

It is important to note that the session is by no means the first of its kind at SIGGRAPH nor at other conferences. Many different session types have attempted to deepen our understanding of how we can improve academic and research partnerships. NSERC Engage grants are just one example of a growing number of triple helix models (government-industry-academic) that support just these types of initiatives. Business Symposium attendee Dr. Bernhard Riecke noted that he “really enjoyed the direct interaction at the roundtable session with different people from different backgrounds, and having a concrete facilitated brainstorming session helped to make it constructive and find shared values and goals between industry and academia. It’s exactly the kind of conversation I wish would happen more between industry and academia.”

A number of articles have been written about the subject of industry and academic collaboration. I draw predominantly from the recent literature that underlines the importance of transforming the relationship between academics and any industry from one of researchers providing a service to one where there is equal partnership, stake, alignment, and a clearly defined value proposition on both sides. One such paper from researchers in Sweden discusses three important considerations in the development of research relationships, “since the process of knowledge creation is conceived of as an interactive and cooperative one.” These include the following “critical aspects:” (a) the partnership-building process itself, (b) understanding the “nature of the collaborative research process,” and (c) identifying and understanding the “challenges involved” in working together . While the authors take the position of understanding challenges associated with the relationship from the point of view of the researcher, the goal of the Business Symposium session was not to focus on the reasons why more successful collaborations do not materialize. There are many success stories. What was important was to understand the characteristics that contributed to those success stories, in order to motivate more collaboration by ensuring that the points of view of both industry and academic researchers were heard.

Recapping the Panel

In the first part of the session, panelists discussed many of the prevalent themes that were later affirmed during the roundtable discussions. These themes became important considerations for the goal of developing and nurturing long-term relationships between industry and academic partners, including:

- Understand one another’s needs clearly and to be explicit about them.

- Be aligned on identifying and communicating objectives prior to moving forward on any research initiative.

- Define and understand the different types of research that are possible.

- Have someone embedded in a company that can act as liaison between researcher(s) and employees at that company. This person will also act as a sort of translator of some of the language and purpose of research.

- Be clear on the advantages and disadvantages of both short- and long-term research cycles, define the duration of a research cycle, and understand how the collection and analysis of data might benefit both parties in either case, and why.

- As a company, be prepared to invest time in helping to define the research initiative, as well as devote some time to the interaction and relationship building with the researcher in addition to graduate students who will be associated with the initiative.

- Work together to identify and apply for a variety of government funding sources, such as those that exist in BC and Canada, including NSERC, SSHRC Engage, CIHR grants, and the internship support provided by MITACS.

The entire panel discussion was graphic-recorded by artist, musician, educator, and co-chair of Vancouver’s Sketching in Practice symposium Jason Toal (pictured above).

Roundtables and Mindstorms

The second part of the session consisted of two components and included the following prompts to inspire discussion:

What Research Would Benefit Our Organization?

Participants were guided to brainstorm areas of research they were interested in that may improve their organization’s understanding of its own processes, a new market they wished to target, a new product they wished to develop, etc. The simple format of a mind map with a central theme of research at the center was used.

Graphic by MDM Program Graduate John Bondoc

Identifying Common Needs

Participants re-mapped previously uncovered areas of research they were interested in. These were contrasted with the needs of academic researchers who were invited to be present.

Graphic by MDM Program Graduate John Bondoc

Community Support

To compensate for a short amount of time, which would make it challenging for participants to write their ideas down quickly while simultaneously involved in intense conversation, a team of 13 graduate students from the University of British Columbia’s Master of Digital Media program were invited to support participants by creating graphic recordings of their thoughts and ideas on paper.

CDM graduate student John Bondoc with Microsoft’s Charla Pereira

Photo by: Melissa Guzman © 2018 ACM SIGGRAPH

Since the variety and types of research partnerships are vast and highly dependent on researcher industry contextual partnership, it was important to position the session as one that offered the opinions and experiences of multiple voices. For this reason, additional researchers from University of British Columbia (UBC), Simon Fraser University (SFU), Emily Carr University of Art and Design, and University of Victoria were invited to sit at different tables with members of the digital media industry to answer questions regarding different types of research partnerships they were engaged in, and actively support discussions about research partnership. Those participants included: Dr. Bernhard Riecke, VR researcher and consultant; Dr. Wolfgang Stuerzlinger, 3D and spatial user interface designer and researcher; Maria Lantin, artist, researcher, and programmer; Dr. Yvonne Coady, professor of computer science; Alan Goldman, adjunct researcher and industry liaison; Ben Chow, part of SFU’s industry engagement team; and, Dr. Richard Smith, researcher and director of the Master of Digital Media program. As Vivian Chan, one of the lead organizers of the Symposium recounted, “I was impressed and honored that many of the leading researchers and experimenters in BC’s post-secondary attended this event to share their expertise. It’s a true testament to the commitment of Canadian researchers to want to partner with industry.”

In retrospect, Smith recalled being “impressed by the (unusual for conferences) requirement to sit with people we didn’t already know, the break for discussion, actual work in-between speakers, and the opportunity to report back to the room the outcome of those discussions. A very useful and positive innovation.”

Dr. Bernhard Riecke with industry attendees

Photo by: Melissa Guzman © 2018 ACM SIGGRAPH

Roundtable Results

The roundtable discussions yielded some interesting data. As mentioned earlier, many of the themes brought up by the panelists were also uncovered during the discussions by participants. The result can be categorized into three dominant areas of discussion: (1) pre-research phase in which all stakeholders align and come to agreement on how a research partnership will benefit all parties, a discussion of timeline, an open discussion on ownership of IP, the importance of involving graduate students in the research process, how the research will be financed often influencing start-time, and pre-agreement on the dissemination of data; (2) in-research phase in which all stakeholders align on persistent communication and attention to the research process throughout the research cycle, reflection, or retrospection at the completion of each research cycle, roles, and responsibilities, as well as rules of play; and, (3) post-research phase in which all stakeholders align on the dissemination of data to the public and for peer review, and internships and possible hiring of graduate students on the research team, intellectual property, and commercialization.

Recurring themes included:

- Understanding the value of research and how it might benefit an organization and a researcher at an academic institution. The research design, when carefully crafted could also be used to deepen a company’s cultural values through participatory design processes. These participatory design methodologies were discussed at various tables and opened up the possibility of more value for some company members present. Researchers also benefit in multiple ways when initiatives open new opportunities not previously considered. These opportunities can present themselves when a company has a specific request that may not align with existing research agendas. It is therefore up to each researcher to determine both the short- and long-term benefits of partnering with a company especially if the researcher has the ability to be more flexible. Flexibility and adaptability after research had already begun also seemed to be a motivating factor for collaboration for many of the attendees.

- Deconstructing research timelines. While assumptions of long research timelines surfaced, participants had the opportunity to dig deeper into exceptions to the rule. The traditional view of research is that it is a long, drawn-out process whose analysis of data is slow compared to the pace of change that a company is seeking. Conversations, however, showed that long-term research is not the only type of research that exists. In fact, there are many rapid research methodologies that can serve product design, user-testing, and be used to validate user experience choices made by a design team in production. Companies have to be more clear as to what type of research will most benefit their own initiatives and this requires a bit of digging around as to what is out there, who has used it, etc. One paper mentioned “action research” as a qualitative methodology that might best align with agile sprint cycles adopted by many digital media companies. This is because of its cyclic process of planning, acting, observing, and reflecting on data. Agile teams integrate this process naturally when developing prototypes in their never-ending pursuit of improving user experience (UX), for example. Many types of action research recognize a process in which all members of a team or organization become equal participants in the research process itself, increasing transparency and buy-in. Action research, like other qualitative methodologies are increasingly complementing the need for quantitative data in organizational research. In the moving target of UX research, researchers and UX teams versed in conducting user-testing can learn from one another, in defining and developing a more rigorous process while understanding how to lessen bias through “triangulation, thick description, peer reviews, and external audits” (Creswell & Miller, 2016, p. 125).

Industry participants at the Business Symposium

Photo by: Melissa Guzman © 2018 ACM SIGGRAPH

- Engaging in persistent communication throughout a collaboration. For attendees, this meant drawing up a communication plan ahead of time, agreeing on it, and working together to ensure that regular communication could move projects forward. If same-time/same-place interactions proved challenging, Slack and other social collaboration tools were mentioned as important ways to ensure persistent check-ins and reporting of progress.

- The importance of bearing in mind that researchers also come with graduate students who they want to create opportunities for. If industry is interested in working with academic researchers, whatever the value proposition, they also need to understand and be comfortable becoming a partner in the teaching and learning ecosystem that comes with the post-secondary territory. Researchers are often working with a number of graduate students on large initiatives and the advantages of working with graduate students outweigh the potential pitfalls. A research partnership is a great way to assess the capabilities and potential of students who may be considered as future hires for the company or potential interns if internships and/or co-ops form part of their course work. In addition, graduate students will likely be spending much more time directly involved in the research design, interfacing with an industry partner and disseminating the results of data analysis. This is important to grasp, as an industry partner needs to be open to spending more time on the project and not simply expect the work to be completed with no reciprocal teaching and learning opportunities to be offered throughout research cycles. Likewise, increasing the stakes for students of having to collaborate with a real-world partner versus solely working on a lab project in the conduct of pure research, will also increase the learning opportunities (negotiation, presenting ideas, improving the articulation of their ideas, making complicated research language more accessible, and understanding how what they are designing/learning/researching, can be applied to solve ill-structured (or wicked) real-world problems).

A Conclusion

While many of the attendees were eager to begin some type of research partnership, there were still some unresolved matters that were brought up in some of the discussions and on the panel. One of the most relevant was implied through a simple question: Where do I begin if I want to initiate a research collaboration with a researcher at an academic institution?

It seemed trivial to simply say, “Well, right here.” But, in fact, one approach is to attend conferences and meetups where those initial in-person connections can be made, like at SIGGRAPH. As is true in other contexts, you can’t beat in-person meetups as first impressions can lead to future collaboration, or to a clear reason not to engage in partnership. Universities can also support an increase in collaboration by hosting sessions with specific industry verticals more regularly and encourage interested academic researchers in committing to those meetups. UBC and SFU have been progressively more active in doing so. Inter-institutional communities of practice, such as Emerging Media BC, hold regular NSERC-sponsored events to seed new research partnerships between industry and academic researchers, and Saeed Dyanatkar, executive producer and manager at the UBC Emerging Media Lab and member of the UBC Studio team, offer regular meetups, workshops, and research presentations with a roster of academics and industry representatives presenting.

The daunting question of “how will we pay for this?” will always manifest, and researchers should be prepared to identify targeted government initiatives that support collaboration between industry and academic researchers so they are able to guide an industry representative to those triple-helix options, including the affordances and the constraints. Companies need to be ready to invest money and human resources, and understand the value proposition clearly, beyond the refrain that any investment needs to justify the ROI. And yes, the value of the partnership needs to be clearly identified before the collaboration begins, but both parties need to anticipate and acknowledge the likely possibility that new advantages will surface during the collaboration as well. A SWOT analysis can be done with both researcher and industry representatives present, so that everyone is aware of the potential risks and rewards.

Dr. Patrick Pennefather is co-appointed at UBC Theatre and Film and the Master of Digital Media program with a focus on project-based learning and a track record of supervising over 250 grad students on 45 successful industry-academic real-world projects producing scalable digital media prototypes for Microsoft, EA, BCLC, Ubisoft, Kabam, Blackbird, small stage, and more.

Leave a Reply